Nonverbal behaviors are an important element of impression formation. How one does something often provides important information to those observing. Affect Control Theory (ACT), an extension and formalization of the ideas of impression formation, is well suited to the inclusion of nonverbal behaviors. Using the framework of ACT, I created event descriptions that incorporated nonverbal behaviors as well as actors, behaviors and objects. I find that nonverbal behaviors do play an important - and independent - part in the creation of impressions.

Nonverbal behaviors, especially in conjunction with other behaviors, are important parts of situational definition. How a person does or says something is bound to affect what others think of the person and his or her action. For example, the teenager who rolls her eyes while setting the dinner table will be viewed differently than the one who does so with a smile.

Social psychologists, including many symbolic interactionists, have recognized the importance of nonverbal behaviors in situational definition. This has been especially true in the areas of deceptive behavior (e.g., Ekman 1985 and Krauss 1981) and expressive cues (e.g., Riggio and Friedman 1986 and Friedman and Miller-Herringer 1991). Affect Control Theory (ACT) (Heise 1979, 1985, 1988), a formalization of symbolic interactionism, has not yet incorporated this important aspect of impression formation.

ACT is especially well suited to the inclusion of the study of nonverbal behaviors because it has a flexible framework of event components that allows for the inclusion of additional elements. ACT uses ideas from symbolic interactionism to explain how definitions of situations lead to specific behaviors and particular emotions. The theory posits that people have meanings for identities and actions, and that these meanings are maintained in interaction. At this time, ACT’s behavioral treatment does not adequately encompass nonverbal behaviors that occur along with other behaviors, although it does address a limited number of nonverbal behaviors as the main behavior of an event. This project will both increase our understanding of the role of nonverbal behaviors in impression formation and increase the utility of ACT in predicting situational definitions.

I first review the principles of Affect Control Theory, demonstrating its usefulness in predicting behavioral and emotional responses to situations. Next, I review the extensions that have already been made. I then describe a new one, the addition of nonverbal behaviors, which I believe will be especially fruitful - both practically and theoretically.

In any situation, individuals see themselves and the others around them as enacting roles or identities. The process of defining situations involves locating “the appropriate identities for self and others at a given time and place” (Heise 1988:2). The appropriate identities are often determined by institutional structures (Smith-Lovin and Douglass 1990), e.g., student. Sometimes, however, identities are less institutional, like “ethical person.” The labeling of identities for all actors in a situation, while not fixed and unchanging, yields a definition of the current situation.

Once the situation is defined for an actor, that definition serves to identify “events” as behaviors that relate two or more identities. Event recognition entails “a process in which a person scans actor-object combinations, examining the potential of each as a frame for a possible event” (Heise 1979:9). Cultural rules tell us what realm of behaviors might be appropriate for specific actors (persons performing behaviors) in each given situation. These rules allow us to eliminate the vast majority of possible behaviors and identify the actual event that is taking place. Further, many events can be discounted from further consideration if they are relations between identities of no importance to us and if the event does not disrupt prior, out-of-context, beliefs held about those identities (Heise 1988). These out-of-context affective beliefs are called fundamental sentiments.

ACT quantifies the definitions of actors and behaviors on three dimensions: Evaluation, Potency and Activity (EPA) that have been shown to be human universals for responding to stimuli (Osgood, May and Miron 1975). These dimensions capture the cognitive responses of human beings to external persons, things and actions. Evaluation measures sentiments of goodness versus badness. Potency indicates powerfulness versus powerlessness. Activity corresponds to liveliness versus passiveness. Identities and behaviors have fundamental EPA sentiment ratings for a culture.

ACT measures each dimension (E, P and A) on an interval scale with the extremes of –4.33 to +4.33 (see Schneider 2002 for a detailed description of the measurement procedure). For example, in the United States, “mother” is seen as quite good (2.4), fairly powerful (1.4) and fairly active (1.3). “Provoke” has the fundamental ratings of -1.2, 0.3 and 0.7. Thus, this action is seen as fairly bad, neither powerful or weak and slightly active. Often these measures are simply collapsed into either positive or negative ratings on each dimension, resulting in eight profiles: E+ P+ A+; E+ P+ A-; E+ P- A+; E+ P- A-; E- P+ A+; E- P+ A-; E- P- A+; and E- P- A-.

Events produce transient impressions for actors and observers that can temporarily alter the EPA ratings for any part of the scenario: actor, behavior or other. In other words, “events change people’s feelings about things” (Smith-Lovin 1988). These transient impressions, or event-generated, in-context feelings, may be quickly changed by subsequent events or redefinitions (MacKinnon 1994).

Averrett and Heise (1988) conducted a study to add modifiers to identities within ACT. These identity modifiers include such things as statuses, personality traits and mood descriptors, which can be long-term individual characteristics or temporary states. Statuses include things like rich, young or black. Dispositions (e.g., introverted) and styles make up personality traits. Angry, proud and shaken are examples of moods.

Averrett and Heise (1988) collected EPA ratings for 64 combinations of modifiers and behaviors. They then modeled how the impressions that these combinations formed could be predicted from the original meanings associated with the identity and the modifier. For example, the evaluation rating of the combination was:

Ce = .17 + .62Pe - .14Pp - .18Pa + .50Re

where Pe is the fundamental evaluation sentiment for the modifier, Pp is the fundamental potency sentiment for the modifier, Pa is the fundamental activity sentiment for the modifier and Re is the fundamental evaluation sentiment for the identity. They also examined how these combined identities affected the formation of impressions for identities in the contexts of events. The combinations acted just like unmodified identities in the context of events. In other words, the EPA meaning of the composite could be substituted for Ae, Ap and Aa in a transient impression equation.

Settings

Smith-Lovin (1988) extended Affect Control Theory by examining how behavior changes from one setting to another. She first examined the EPA ratings for certain settings. Then, these settings were combined with different actor-behavior-object combinations to determine whether the settings affected the transient impressions of those identities and behaviors. Lastly, she assessed the usefulness of the inclusion of settings in the general ACT model.

Interesting and reasonable results were obtained through impression change equations when settings were added to the model, indicating that settings do form a part of event identification for actors and observers and therefore influence subsequent behaviors and emotions. Particularly, settings that are high on activity produce higher evaluation ratings for those who are in them. Additionally, the ratings of settings were examined and it was found that the behavior performed in a given setting caused that setting’s rating to be adjusted accordingly. Actors strive to maintain the meanings of settings as well as the meanings of identities and actions.

I examine nonverbal behaviors that occur in conjunction with other actions. I propose to extend ACT by incorporating these nonverbal behaviors into the equations predicting transient impressions. Nonverbal behaviors that coincide with other actions can help to describe and clarify how the actor performs the action; in other words, nonverbal behaviors inform observers about how the subject feels about performing the behavior.

Nonverbal behaviors are those aspects of a person’s demeanor that communicate additional information about the behavior being performed. For example, nonverbal behaviors tell others whether a subject is performing a behavior enthusiastically (with a smile) or reluctantly (with a roll of the eyes). Several nonverbal behaviors can occur together (as one nonverbal behavior set) to more accurately convey how the behavior is being performed.

Nonverbal behaviors performed with behaviors could either reinforce the meanings of those behaviors or contradict them. In either case, I anticipate that nonverbal behaviors will affect the meaning of the behavior. Therefore, it may also affect the impressions of the actor and recipient of the behavior. Nonverbal behaviors may work as amalgamations with the other behaviors, as Averett and Heise (1988) found with modifiers and identities, or they may work independently.

This is a study with written stimuli. The stimuli were comprised of sets of events. Each event was a complete sentence including a subject identity, a behavior, a nonverbal behavior and an object identity.

Completely crossing all of the variables would be impossible (eight actor profiles x eight object profiles x eight nonverbal behavior profiles x eight behavior profiles = 4096 possible events). Instead, I employed a design that provides maximum variation on these variables while limiting the actual number of events to a feasible number. Thus, I do not need to create and study all possible combinations in order to examine the impression formation process.

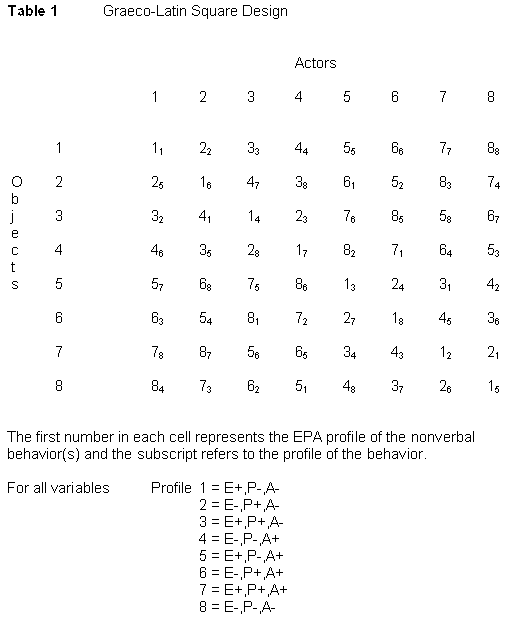

The event set has an 8x8 Graeco-Latin square design, shown in Table 1. This design requires four independent variables. All four variables must have the same number of levels for the maximization of variation to occur. For this study I have eight levels of the independent variables--the eight combinations of three two-level factors, which is one normal permutation of the design (Fisher and Yates 1963). Evaluation, potency and activity are the three factors; a rating as positive or negative created the two levels. As stated above, taken together the EPA ratings yield eight configurations. This design yields sixty-four events, a much more manageable number. These sixty-four events were broken down into eight subsets, with each subset containing the events from one row of the Graeco-Latin square table.

In creating the events, I employ identities, nonverbal behaviors and behaviors that fit the eight EPA configurations most strongly (i.e., have among the most extreme ratings on the three dimensions) and that are logically useful in describing a large number of events. Standard ratings on fundamental meanings are available for actors, behaviors and objects. The appendix to Heise (1979) lists ratings for hundreds of identities and behaviors. That list provided the actor and object-person identities and the behaviors in the stimuli here. The ratings obtained in an earlier study on nonverbal behaviors (Rashotte 2002) identify the nonverbal behavior fitting each profile.

Respondents were paid volunteers recruited from undergraduate courses. After scheduling by telephone, they came to the Sociology Department and sat around a work-table to fill out the stimuli. Instructions appeared both in writing and orally, and included a request not to communicate or to look at others’ ratings until after all respondents had finished with their work. The researcher was present to ensure that subjects did not discuss responses. I excluded students who had participated in previous studies. Approximately 20 respondents rated each subset of events with even numbers of males and females.

Response sheets contained the standard nine-point scales for Evaluation, Potency and Activity. Each event element from each event was rated on these dimensions. Thus, if the event were “Mother smiles and plays with baby,” then “mother,” “plays with,” “smiles” and “baby” would get each rated on evaluation, potency and activity within the context of this event.

The inclusion of nonverbal behaviors in the equations of ACT requires predicting transient (in-context) ratings of event elements using the fundamental sentiments associated with the actor, behavior, nonverbal behavior and object of each event. This is done using ordinary least-squares regressions. I am primarily interesting in determining which event elements are significant in producing each of the transient impressions and in examining the role that nonverbal behaviors play in that impression formation.

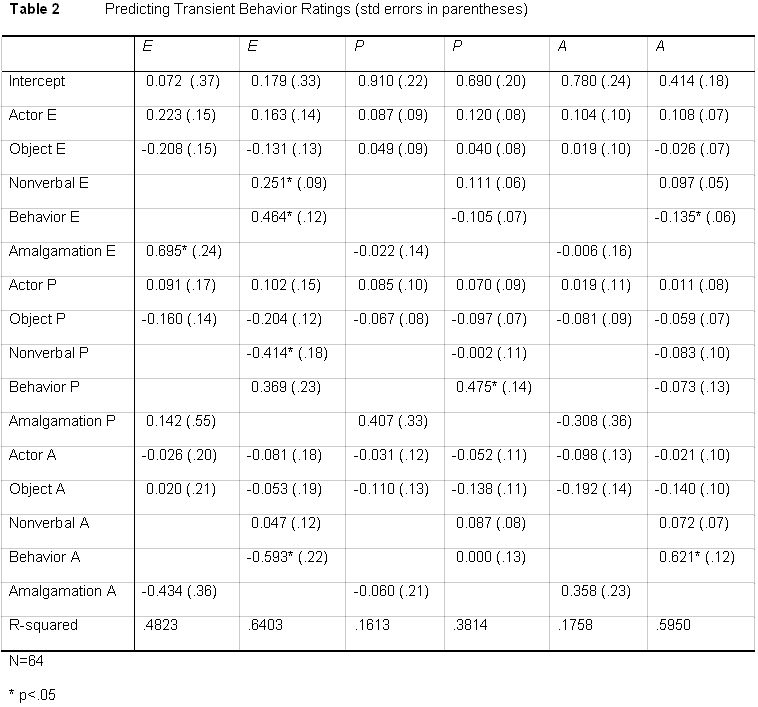

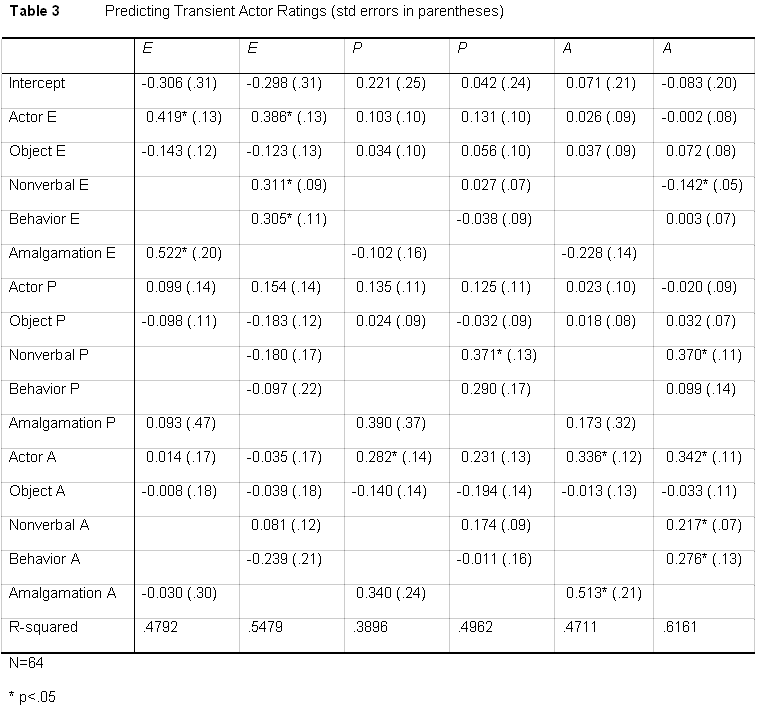

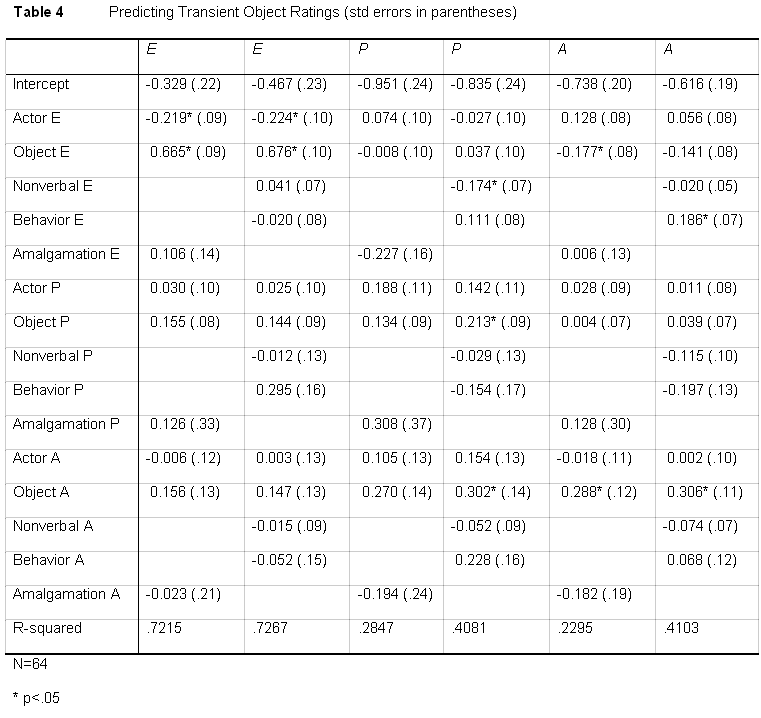

Tables 2, 3 and 4 present the regression coefficients for predicting in-context behavior, actor and object ratings, respectively. In each table, models are displayed predicting the evaluation, potency and activity ratings. Two models predict each of those dimensions; one model treats the behavior and nonverbal behavior as an amalgamation, following the work of Averett and Heise (1988), and the other model treats those elements separately.

By looking at the R-squared values in Table 2, it is clear that the models that treat the behavior and nonverbal behavior separately are more predictive of in-context behaviors ratings than those that treat those elements as amalgamations. This is true for all three dimensions, Evaluation, Potency and Activity. Therefore, I will restrict further comments to the “separate elements” models.

In predicting the behavior’s transient evaluation rating, four separate elements have significant effects. As would be expected, the behavior’s fundamental evaluation rating has a positive effect. In addition, the evaluation of the nonverbal behavior that accompanies the behavior also has a positive impact. Doing the behavior in a nice way makes the behavior seem nicer. The nonverbal behavior’s potency rating, however, has a negative effect on the behavior’s evaluation. Doing something in a strong way makes it seem less nice. Finally, the behavior’s fundamental activity rating also has a negative effect on the behavior’s in-context evaluation rating. Active behaviors seem less nice.

The prediction of the behavior’s in-context potency rating is much simpler. It only depends on the behavior’s fundamental potency rating. As expected, this is a positive effect.

In predicting in-context activity for behaviors, two elements had significant effects. Once again, as would be expected the fundamental rating for that dimension for the behavior has a positive effect. Additionally, however, the behavior’s evaluation rating has a negative effect. As above, we see a negative relationship between a behavior’s niceness and its liveliness.

For actors, as with behaviors, the models that treat the behaviors and nonverbal behaviors as separate elements are more predictive on every dimension than those that utilize amalgamations. Therefore, I again limit the discussion to the separate elements models. Table 3 presents all of these models.

In predicting actors’ evaluation ratings, three elements are significant. First, as expected, is the actors’ fundamental evaluation rating. In addition, the evaluation ratings of the behavior and the nonverbal behavior have effects. Doing nice things makes a person seem nicer.

The only variable to have a significant consequence for the actor’s potency ratings in-context is the nonverbal behavior’s potency. Here again, we see that a person’s demeanor, here as it relates to powerfulness, affects what others think of him/her. Performing more powerful nonverbal behaviors increases a person’s powerfulness rating.

Actors’ activity ratings are very multidimensional. The actor’s fundamental activity rating has a positive effect on the actor’s in-context rating. Also, the activity ratings of the behavior and the nonverbal behavior are significant in a positive direction, indicating that doing active things makes a person seem more active. In addition, both the evaluation rating and the potency rating of the nonverbal behavior have effects on the actor’s in-context activity rating; evaluation is negative and potency is positive. Performing good nonverbal behaviors makes one seem less active; doing strong nonverbal behaviors makes one seem more active.

Once again, for objects, as with actors and behaviors, the separate elements model is more predictive on all three dimensions than the amalgamation model. This can be seen in Table 4. Only the separate elements models, therefore, will be discussed here.

In predicting the objects person’s in-context evaluation rating, there are two significant elements. One, as would be expected, is that identity’s fundamental meaning on the evaluation dimension, which has a positive effect. The other is the actor’s fundamental evaluation meaning, which has a negative effect. When a good person acts toward an object person, the object person seems less good.

An object’s in-context potency rating is affected by three elements. First, again as would be expected, that identity’s out-of-context potency rating has a positive effect. In addition, the identity’s out-of-context activity rating has a positive effect, such that active object persons seem more powerful. Finally, the nonverbal behavior’s fundamental evaluation rating has a negative effect. When an actor has a negative demeanor, the object of their behavior seems more potent.

The final model in Table 4 shows the regression for predicting the object person’s in-context activity rating. As with other activity models, we here see multidimensionality. The object person’s fundamental activity rating, as expected, has a positive effect. In addition, the behavior’s evaluation rating also has a positive effect. Being the object of a good behavior makes one seem more active.

In addition to the models presented in the tables, a series of models were run that included interaction terms. For every dependent variable (E, P and A in-context ratings for behavior, actor and object) a regression was performed that included all of the event elements as well as two-way interaction terms between any significant elements. Only three of these models produced any statistically significant interaction terms. As a whole, interaction terms did not produce any identifiable patterns, so I will not discuss them further here.

Two main facts have emerged from this extension of ACT to include nonverbal behaviors. First, nonverbal behaviors are important parts of the impression formation process and need to be included in future work. This is evidenced by the fact that more than half of the separate elements models include significant effects from nonverbal behavior ratings. Clearly, people are using information about nonverbal behaviors in the creation of situation definitions. Second, the statistical analyses indicate that nonverbal behaviors work somewhat differently in relation to behaviors than modifiers did in relation to actors and objects. In every case, it was more productive to examine behaviors and nonverbal behaviors separately rather than as amalgamations

Affect Control Theory is currently one of the most useful and rigorous frameworks for the understanding of social events. Future work should continue to elaborate and extend this theory to continue to increase its utility. Deeper understanding of the role of nonverbal behaviors will certainly be a part of that future work

Averett, Christine and David R. Heise. 1988. “Modified Social Identities: Amalgamations, Attributions and Emotions.” Pp. 103-132 in Analyzing Social Interaction: Advances in Affect Control Theory, edited by Lynn Smith-Lovin and David R. Heise. New York: Gordon and Breach.

Ekman, Paul. 1985. Telling Lies: Clues to Deceit in the Marketplace, Politics and Marriage. W.W. Norton and Company.

Fisher, Ronald A. and Frank Yates. 1963. Statistical Tables for Biological, Agricultural and Medical Research. Oliver and Boyd.

Friedman, Howard S., and Terry Miller-Herringer. 1991. “Nonverbal Display of Emotion in Public and in Private: Self-Monitoring, Personality, and Expressive Cues.” Journal Of Personality and Social Psychology 61: 766-775.

Greenberg, J. H. 1963. “Some Universals of Grammar with Particular Reference to the Order of Meaningful Elements.” In Universals of Language, edited by J. Greenberg. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Heise, David R. 1979. Understanding Events: Affect and the Construction of Social Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Heise, David R. 1985. “Affect Control Theory: Respecification, Estimation and Tests of the Formal Model.” Journal of Mathematical Sociology 11:191-222.

Heise, David R. 1988. “Affect Control Theory: Concepts and Model.” Pp. 1-34 in Analyzing Social Interaction: Advances in Affect Control Theory, edited by Lynn Smith-Lovin and David R. Heise. New York: Gordon and Breach.

Krauss, Robert M. 1981. “Impression formation, impression management, and nonverbal behaviors.” Pp. 323-41 in Social Cognition: The Ontario symposium, Vol. 1, edited by E. Tory Higgins, C. Peter Herman and Mark P. Zanna. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

MacKinnon, Neil J. 1994. Symbolic Interactionism as Affect Control. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Osgood, Charles E., W. H. May and M. S. Miron. 1975. Cross-Cultural Universals of Affective Meaning. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Rashotte, Lisa Slattery. 2002. “What Does that Smile Mean? The Meaning of Nonverbal Behaviors in Social Interaction.” Social Psychology Quarterly 65: 92-102.

Riggio, Ronald E. and Howard S. Friedman. 1986. “Impression formation: The role of expressive behavior.” Journal of Personality & Social Psychology 50: 421-427.

Schneider, Andreas. 2002. “Computer Simulation of Behavior Prescriptions in Multi-cultural Corporations.” Organization Studies 23: 105-131.

Smith-Lovin, Lynn. 1988. “Impressions from Events.” Pp. 35-70 in Analyzing Social Interaction: Advances in Affect Control Theory, edited by Lynn Smith-Lovin and David R. Heise. New York: Gordon and Breach.

Smith-Lovin, Lynn and William Douglass. 1990. “Modeling Emotions in Religious Ritual: An Affect Control Analysis of Two Religious Groups.” In Social Perspectives on Emotion, edited by David Franks and Viktor Gecas. JAI Press.

© Electronic Journal of Sociology